Hello everyone, Asahi Lina here!✨

marcan asked me to write an article about the M1 GPU, so here we are~! It’s been a long road over the past few months and there’s a lot to cover, so I hope you enjoy it!

What’s a GPU?

You probably know what a GPU is, but do you know how they work under the hood? Let’s take a look! Almost all modern GPUs have the same main components:

- A bunch of shader cores, which process triangles (vertex data) and pixels (fragment data) by running user-defined programs. These use different custom instruction sets for every GPU!

- Rasterization units, texture samplers, render output units, and other bits which work together with the shaders to turn the triangles from the app into pixels on the screen. Exactly how this works varies from GPU to GPU!

- A command processor that takes drawing commands from the app and sets up the shader cores to process them. This includes data like what list of triangles to draw, what global attributes to use, what textures will be used, what shader programs to use, and where the final image goes in memory. It then sends this data over to the shader cores and other units, to program the GPU to actually do the rendering.

- A memory management unit (MMU), which is in charge of limiting access to memory areas belonging to a specific app using the GPU, so different apps can’t crash or interfere with each other.

(This is all very simplified and in reality there are a lot more parts that vary from GPU to GPU, but those are the most important bits!)

In order to handle all these moving parts in a reasonably safe way, modern GPU drivers are split into two parts: a user space driver and a kernel driver. The user space part is in charge of compiling shader programs and translating API calls (like OpenGL or Vulkan) into the specific command lists that the command processor will use to render the scene. Meanwhile, the kernel part is in charge of managing the MMU and handling memory allocation/deallocation from different apps, as well as deciding how and when to send their commands to the command processor. All modern GPU drivers work this way, on all major OSes!

Between the user space driver and the kernel driver, there is some kind of custom API that is customized for each GPU family. These APIs are usually different for every driver! In Linux we call that the UAPI, but every OS has something similar. This UAPI is what lets the user space part ask the kernel to allocate/deallocate memory and submit command lists to the GPU.

That means that in order to make the M1 GPU work with Asahi Linux, we need two bits: a kernel driver and a user space driver! 🚀

Alyssa joins the project

All the way back in 2021 when Asahi Linux started, Alyssa Rosenzweig joined the project to start working on reverse engineering the M1 GPU. Together with Dougall Johnson (who focused on documenting the GPU shader architecture), she started reverse engineering all the user space bits, including the shaders and all the command list structures needed to set up rendering. That’s a ton of work, but less than one month in she was already drawing her first triangle! She’s amazing! If you haven’t checked out her series on dissecting the M1 GPU you should visit her website and take a look! ✨✨

But wait, how can she work on the user space driver without a kernel driver to go with it? Easy, she did it on macOS! Alyssa reverse engineered the macOS GPU driver UAPI enough to allocate memory and submit her own commands to the GPU, and this way she could work on the user space part without having to worry about the kernel bit. That’s super cool! She started writing an M1 GPU OpenGL driver for Mesa, the Linux userspace graphics stack, and just a few months later she was already passing 75% of the OpenGL ES 2 conformance tests, all on macOS!

Earlier this year, her work was so far ahead that she was running games on a fully open source Mesa OpenGL stack, running on top of Apple’s kernel driver on macOS! But there was still no Linux kernel driver… time to help out with that part! ✨

The Mysterious GPU Firmware

In April this year, I decided to start trying to figure out how to write an M1 GPU kernel driver! Scott Mansell had already done a bit of reconnaisance work on that front when I got started… and it was already clear this was no ordinary GPU. Over the first couple of months, I worked on writing and improving a m1n1 hypervisor tracer for the GPU, and what I found was very, very unusual in the GPU world.

Normally, the GPU driver is responsible for details such as scheduling and prioritizing work on the GPU, and preempting jobs when they take too long to run to allow apps to use the GPU fairly. Sometimes the driver takes care of power management, and sometimes that is done by dedicated firmware running on a power management coprocessor. And sometimes there is other firmware taking care of some details of command processing, but it’s mostly invisible to the kernel driver. In the end, especially for simpler “mobile-style” GPUs like ARM Mali, the actual hardware interface for getting the GPU to render something is usually pretty simple: There’s the MMU, which works like a standard CPU MMU or IOMMU, and then the command processor usually takes pointers to userspace command buffers directly, in some kind of registers or ring buffer. So the kernel driver doesn’t really need to do much other than manage the memory and schedule work on the GPU, and the Linux kernel DRM (Direct Rendering Manager) subsystem already provides a ton of helpers to make writing drivers easy! There are some tricky bits like preemption, but those are not critical to get the GPU working in a brand new driver. But the M1 GPU is different…

Just like other parts of the M1 chip, the GPU has a coprocessor called an “ASC” that runs Apple firmware and manages the GPU. This coprocessor is a full ARM64 CPU running an Apple-proprietary real-time OS called RTKit… and it is in charge of everything! It handles power management, command scheduling and preemption, fault recovery, and even performance counters, statistics, and things like temperature measurement! In fact, the macOS kernel driver doesn’t communicate with the GPU hardware at all. All communication with the GPU happens via the firmware, using data structures in shared memory to tell it what to do. And there are a lot of those structures…

- Initialization data, used to configure power management settings in the firmware and other GPU global configuration data, including colour space conversion tables for some reason?! These data structures have almost 1000 fields, and we haven’t even figured them all out yet!

- Submission pipes, which are ring buffers used to queue work on the GPU.

- Device control messages, which are used to control global GPU operations.

- Event messages, which the firmware sends back to the driver when something happens (like a command completing or failing).

- Statistics, firmware logs, and tracing messages used for GPU status information and debugging.

- Command queues, which represent a single app’s list of pending GPU work

- Buffer information, statistics, and page list structures, used to manage the Tiled Vertex Buffers.

- Context structures and other bits that let the GPU firmware keep track of what is going on.

- Vertex rendering commands, which tell the vertex processing and tiling part of the GPU how to process commands and shaders from userspace to run the vertex part of a whole render pass.

- Fragment rendering commands, which tell the rasterization and fragment processing part of the GPU how to render the tiled vertex data from the vertex processing into an actual framebuffer.

It gets even more complicated than that! The vertex and fragment rendering commands are actually very complicated structures with many nested structures within, and then each command actually has a pointer to a “microsequence” of smaller commands that are interpreted by the GPU firmware, like a custom virtual CPU! Normally those commands set up the rendering pass, wait for it to complete, and clean up… but it also supports things like timestamping commands, and even loops and arithmetic! It’s crazy! And all of these structures need to be filled in with intimate details about what is going to be rendered, like pointers to the depth and stencil buffers, the framebuffer size, whether MSAA (multisampled antialiasing) is enabled and how it is configured, pointers to specific helper shader programs, and much more!

In fact, the GPU firmware has a strange relationship with the GPU MMU. It uses the same page tables! The firmware literally takes the same page table base pointer used by the GPU MMU, and configures it as its ARM64 page table. So GPU memory is firmware memory! That’s crazy! There’s a shared “kernel” address space (similar to the kernel address space in Linux) which is what the firmware uses for itself and for most of its communication with the driver, and then some buffers are shared with the GPU hardware itself and have “user space” addresses which are in a separate address space for each app using the GPU.

So can we move all this complexity to user space, and have it set up all those vertex/fragment rendering commands? Nope! Since all these structures are in the shared kernel address space together with the firmware itself, and they have tons of pointers to each other, they are not isolated between different processes using the GPU! So we can’t give apps direct access to them because they could break each other’s rendering… so this is why Alyssa found all those rendering details in the macOS UAPI…

GPU drivers in Python?!

Since getting all these structures right is critical for the GPU to work and the firmware to not crash, I needed a way of quickly experimenting with them while I reverse engineered things. Thankfully, the Asahi Linux project already has a tool for this: The m1n1 Python framework! Since I was already writing a GPU tracer for the m1n1 hypervisor and filling out structure definitions in Python, I decided to just flip it on its head and start writing a Python GPU kernel driver, using the same structure definitions. Python is great for this, since it is very easy to iterate with! Even better, it can already talk the basic RTKit protocols and parse crash logs, and I improved the tools for that so I could see exactly what the firmware was doing when it crashes. This is all done by running scripts on a development machine which connects to the M1 machine via USB, so you can easily reboot it every time you want to test something and the test cycle is very fast!

At first most of the driver was really just a bunch of hardcoded structures, but eventually I managed to get them right and render a triangle!

This was just a hacked up together demo, though… before starting on the Linux kernel driver, I wanted to make sure I really understood everything well enough to design the driver properly. Just rendering one frame is easy enough, but I wanted to be able to render multiple frames, and also test things like concurrency and preemption. So I really needed a true “kernel driver”… but that’s impossible to do in Python, right?!

It turns out that Mesa has something called drm-shim, which is a library which mocks the Linux DRM kernel interface and replaces it with some dummy handling in userspace. Normally that is used for things like shader CI, but it can also be used to do crazier things… so… what if I stuck a Python interpreter inside drm_shim, and called my entire Python driver prototype from it?

Could I run Inochi2D on top of Mesa, with Alyssa’s Mesa M1 GPU driver, on top of drm-shim, running an embedded Python interpreter, sending commands to my Python prototype driver on top of the m1n1 development framework, communicating over USB with the real M1 machine and sending all the data back and forth, in order to drive the GPU firmware and render myself? How ridiculous would that be?

It’s so ridiculous that it worked! ✨

A new language for the Linux kernel

With the eldritch horror Mesa+Python driver stack working, I started to have a better idea of how the eventual kernel driver had to work and what it had to do. And it had to do a lot! There’s no way around having to juggle the more than 100 data structures involved… and if anything goes wrong, everything can break! The firmware doesn’t sanity check anything (probably for performance), and if it runs into any bad pointers or data, it just crashes or blindly overwrites data! Even worse, if the firmware crashes, the only way to recover is to fully reboot the machine! 😱

Linux kernel DRM drivers are written in C, and C is not the nicest language to write complicated data structure management in. I’d have to manually track the lifetime of every GPU object, and if I got anything wrong, it could cause random crashes or even security vulnerabilities. How was I going to pull this off? There are too many things to get wrong, and C doesn’t help you out at all!

On top of that, I also had to support multiple firmware versions, and Apple doesn’t keep the firmware structure definitions stable from version to version! I had already added support for a second version as an experiment, and I ended up having to make over 100 changes to the data structures. On the Python demo, I could do that with some fancy metaprogramming to make structure fields conditional on a version number… but C doesn’t have anything like that. You have to use hacks like compiling the entire driver multiple times with different #defines!

But there was a new language on the horizon…

At around the same time, rumours of Rust soon being adopted officially by the Linux kernel were beginning to come up. The Rust for Linux project had been working on officially adding support for several years, and it looked like their work might be merged soon. Could I… could I write the GPU driver in Rust?

I didn’t have much experience with Rust, but from what I’d read, it looked like a much better language to write the GPU driver in! There are two things that I was particularly interested in: whether it could help me model GPU firmware structure lifetimes (even though those structures are linked with GPU pointers, which aren’t real pointers from the CPU’s perspective), and whether Rust macros could take care of the multi-versioning problem. So before jumping straight into kernel development, I asked for help from Rust experts and made a toy prototype of the GPU object model, in simple userspace Rust. The Rust community was super friendly and several people helped walk me through everything! I couldn’t have done it without your help! ❤

And it looked like it would work! But Rust still wasn’t accepted into mainline Linux… and I’d be in uncharted territory since nobody had ever done anything like this. It would be a gamble… but the more I thought about it, the more my heart told me Rust was the way to go. I had a chat with the Linux DRM maintainers and other folks about this, and they seemed enthusiastic or at least receptive to the idea, so…

I decided to go for it!

Rust beginnings

Since this was going to be the first Linux Rust GPU kernel driver, I had a lot of work ahead! Not only did I have to write the driver itself, but I also had to write the Rust abstractions for the Linux DRM graphics subsystem. While Rust can directly call into C functions, doing that doesn’t have any of Rust’s safety guarantees. So in order to use C code safely from Rust, first you have to write wrappers that give you a safe Rust-like API. I ended up writing almost 1500 lines of code just for the abstractions, and coming up with a good and safe design took a lot of thinking and rewriting!

On August 18th, I started writing the Rust driver. Initially it relied on C code for the MMU handling (partially copied from the Panfrost driver), though later I decided to rewrite all of that in Rust. Over the next few weeks, I added the Rust GPU object system I had prototyped before, and then reimplemented all the other parts of the Python demo driver in Rust.

The more I worked with Rust, the more I fell in love with it! It feels like Rust’s design guides you towards good abstractions and software designs. The compiler is very picky, but once code compiles it gives you the confidence that it will work reliably. Sometimes I had trouble making the compiler happy with the design I was trying to use, and then I realized the design had fundamental issues!

The driver slowly came together, and on September 24th I finally got kmscube to render the first cube, with my brand new Rust driver!

And then, something magical happened.

Just a few days later, I could run a full GNOME desktop session!

Rust is magical!

Normally, when you write a brand new kernel driver as complicated as this one, trying to go from simple demo apps to a full desktop with multiple apps using the GPU concurrently ends up triggering all sorts of race conditions, memory leaks, use-after-free issues, and all kinds of badness.

But all that just… didn’t happen! I only had to fix a few logic bugs and one issue in the core of the memory management code, and then everything else just worked stably! Rust is truly magical! Its safety features mean that the design of the driver is guaranteed to be thread-safe and memory-safe as long as there are no issues in the few unsafe sections. It really guides you towards not just safe but good design.

Of course, there are always unsafe sections of code, but since Rust makes you think in terms of safe abstractions, it’s very easy to keep the surface area of possible bugs very low. There were still some safety issues! For example, I had a bug in my DRM memory management abstraction that could end up with an allocator being freed before all of its allocations were freed. But since those kinds of bugs are specific to one given piece of code, they tend to be major things that are obvious (and can be audited or caught in code review), instead of hard-to-catch race conditions or error cases that span the entire driver. You end up reducing the amount of possible bugs to worry about to a tiny number, by only having to think about specific code modules and safety-relevant sections individually, instead of their interactions with everything else. It’s hard to describe unless you’ve tried Rust, but it makes a huge difference!

Oh, and there’s also error and cleanup handling! All the error-prone goto cleanup style error handling to clean up resources in C just… vanishes with Rust. Even just that is worth it on its own. Plus you get real iterators and reference counting is automatic! ❤

Joining forces

With the kernel driver on the right track, it was time to join forces with Alyssa and start working together! No longer bound by the confines of testing only on macOS, she started making major improvements to the Mesa driver! I even helped a little bit ^^

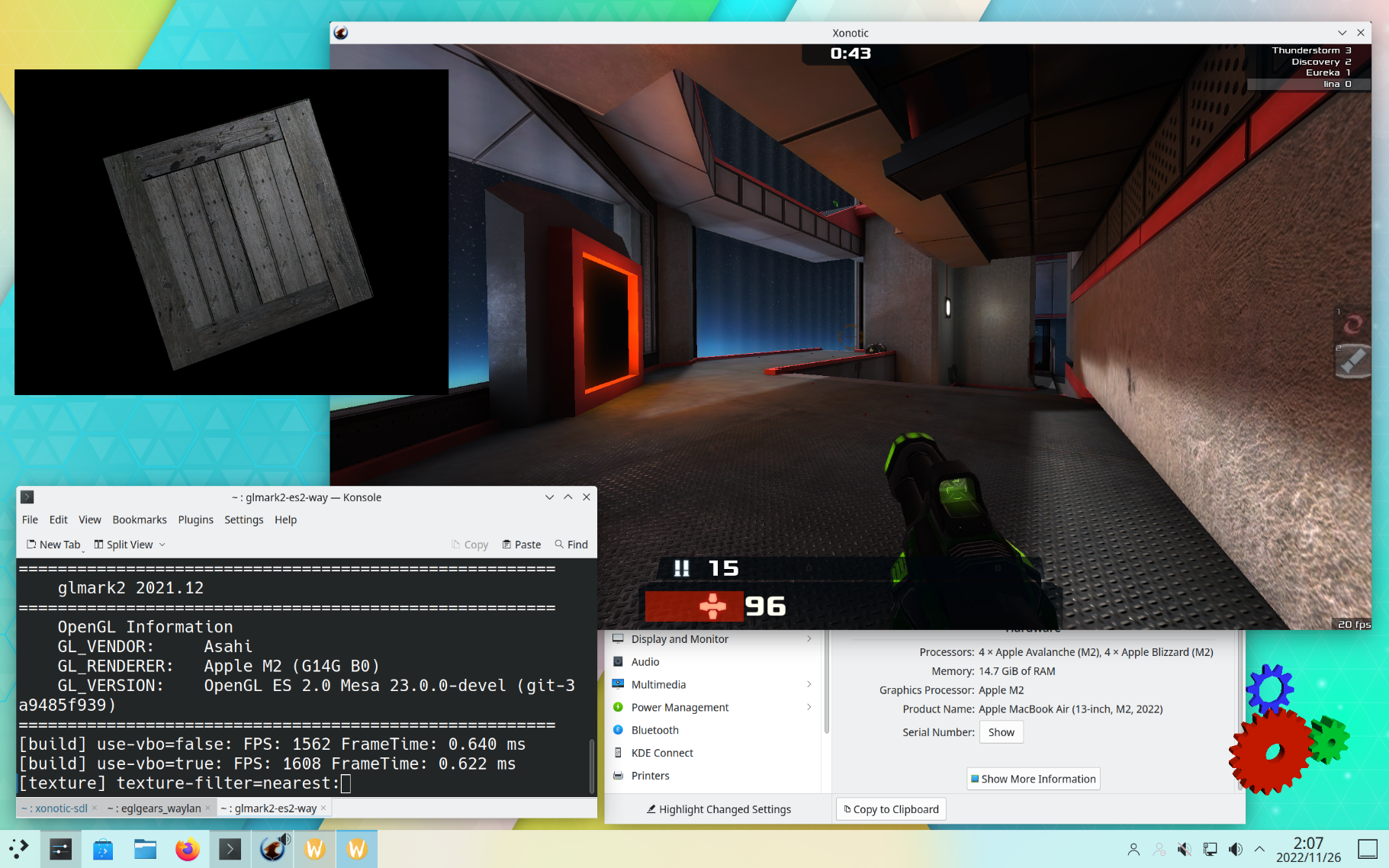

We gave a joint talk at XDC 2022, and at the time we ran the entire talk on an M1 using our drivers! Since then we’ve been working on adding new features, bug fixes, and performance improvements to both sides. I added support for the M1 Pro/Max/Ultra family and the M2 to the kernel side, as well as more and better debugging tools and memory allocation performance improvements. She’s been steadily improving GL conformace, with OpenGL ES 2.0 conformance practically complete and 3.0 conformance at over 96%! She also added many new features and performance improvements, and today you can play games like Xonotic and Quake at 4K!

And since the GPU power management is handled by the firmware, all that just works. I tested Xonotic at 1080p inside a GNOME session, and the estimated battery runtime was over 8 hours! 🚀

What about Vulkan support? Don’t worry… Ella is working on that! ✨✨

What’s next?

There is still a long road ahead! The UAPI that we are using right now is still a prototype, and there are a lot of new features that need to be added or redesigned in order to support a full Vulkan driver in the future. Since Linux mandates that the UAPI needs to remain stable and backwards compatible across versions (unlike macOS), that means that the kernel driver will not be heading upstream for many months, until we have a more complete understanding of the GPU rendering parameters and have implemented all the new design features needed by Vulkan. The current UAPI also has performance limitations… it can’t even run GPU rendering concurrently with CPU processing yet!

And of course there is still a lot of work to do on the userspace side, improving conformance and performance and adding support for more GL extensions and features! Some features like tesselation and geometry shaders are very tricky to implement (since they need to be partially or fully emulated), so don’t expect full OpenGL 3.2+ for quite a long time.

But even with those limitations, the drivers can run stable desktops today and performance is improving every week! Wayland runs beautifully smoothly on these machines now, just like the native macOS desktop! Xorg also works well with some improvements I made to the display driver a few days ago, although you can expect tearing and vsync issues due to Xorg design limitations. Wayland is really the future on new platforms! 💫

So where do you get it? We’re not quite there yet! Right now the driver stack is complicated to build and install (you need custom m1n1, kernel, and mesa builds), so please wait a little bit longer! We have a few loose ends to tie still… but we hope we can bring it to Asahi Linux as an opt-in testing build before the end of the year! ✨✨

If you’re interested in following my work on the GPU, you can follow me at @lina@vt.social or subscribe to my YouTube channel! Tomorrow I’m going to be working on figuring out the power consumption calculations for the M1 Pro/Max/Ultra and M2, and I hope to see you there! ✨

If you want to support my work, you can donate to marcan’s Asahi Linux support funds on GitHub Sponsors or Patreon, which helps me out too! And if you’re looking forward to a Vulkan driver, check out Ella’s GitHub Sponsors page! Alyssa doesn’t take donations herself, but she’d love it if you donate to a charity like the Software Freedom Conservancy instead. (Although maybe one day I’ll convince her to let me buy her an M2… ^^;;)